Research Study 1

Fig. 1.

Navanax inermisCourtesy Kevin Lee, Fullerton, California diverkevin

The cephalaspidean Navanax inermis (Fig. 1) occurs from northern California to the southern limits of the Gulf of California. It is a predator of other opisthobranchs, most notably other shelled species, but may even prey upon conspecifics. If attacked, Navanax releases a yellow hydrophobic substance from a “yellow gland” near its anus directly onto its slime trail. The secretion does not dilute in seawater but adheres to the slime trail, which can persist for several days. Other Navanax, perhaps searching for a meal along the slime trail, turn away. The response is well defined, consisting of contraction, turning at an angle greater than 90o, and retreat. Studies at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California show that the substance is a mix of three related conjugated methyl ketones called navenones, synthesised de novo by Navanax. After its release, the depleted navenone supply is topped up within 3 - 7d. The authors describe the secretion as an alarm pheromone, presumably because it communicates a message to conspecifics warning them of danger. However, if its function is to ward off potential predatory species including conspecifics looking for a meal, then its role may be dual: both a defensive chemical and an alarm pheromone.

Sleeper & Fenical 1977 J Amer Chem Soc 99: 7

Sleeper et al. 1980 J Chem Ecol 6: 57

Research Study 2

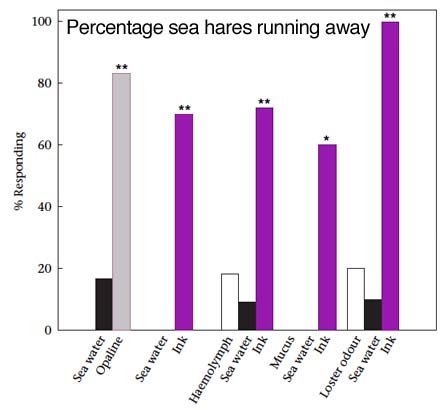

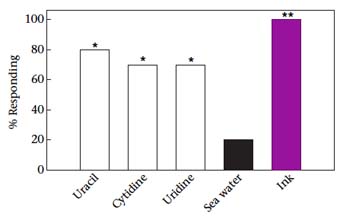

Fig. 1. Escape responses of sea hares Aplysia californica to various secretions and fluids. Sea-hare ink is purple, while opaline secretion, in species that have it, is grey. Absence of bars in the histogram indicate no response. Asterisks indicate significant difference from seawater controls, incuded as part of each test. Other test solutions used are hemolymph, mucus, and lobster odour

Escape running of sea hares Aplysia californica in response to various secretions and chemicals isolated from them

Like many other gastropods, the sea hare Aplysia californica will run from predators or from the scent of alarm chemicals such as ink and opaline secretions remaining behind after a conspecific is damaged or killed. The escape crawling can be quite quick, and often takes the form of a lively “galloping”. While both ink and opaline secretion willl evoke the alarm response, other conspecific fluids such as mucus or hemolymph will not, nor will odours from known predators such as spiny lobsters (Fig. 1). The active components of ink and opaline secretion have been identified by researchers in Maryland and Georgia as the base uracil and the nucleosides uridine and cytidine (Fig. 2). Each molecule alone will elicit a full escape response, while ink without these molecules will not. All three molecules are highly polar and, of course, water soluble. Interestingly, ink from congenor sea hares A. juliana and A. dactylomela, and ink from certain squids and octopuses, also contain uracil and uridine, and all elicit escape behaviours in A. californica. The authors suggest a common evolutionary selection for these chemicals in these distantly related molluscan species.

NOTE other known pheromones in sea hares include four involved in reproduction: attractin, enticin, temptin, and seductin. The names are a bit over the top, but certainly evocative

NOTE the authors seem unclear whether the octopus species they used in the study is Octopus vulgaris or O. bimaculoides

Kicklighter et al. 2007 Animal Behaviour 74: 1481

Nudibranchs & relatives

Nudibranchs & relatives